Introduction

Overview

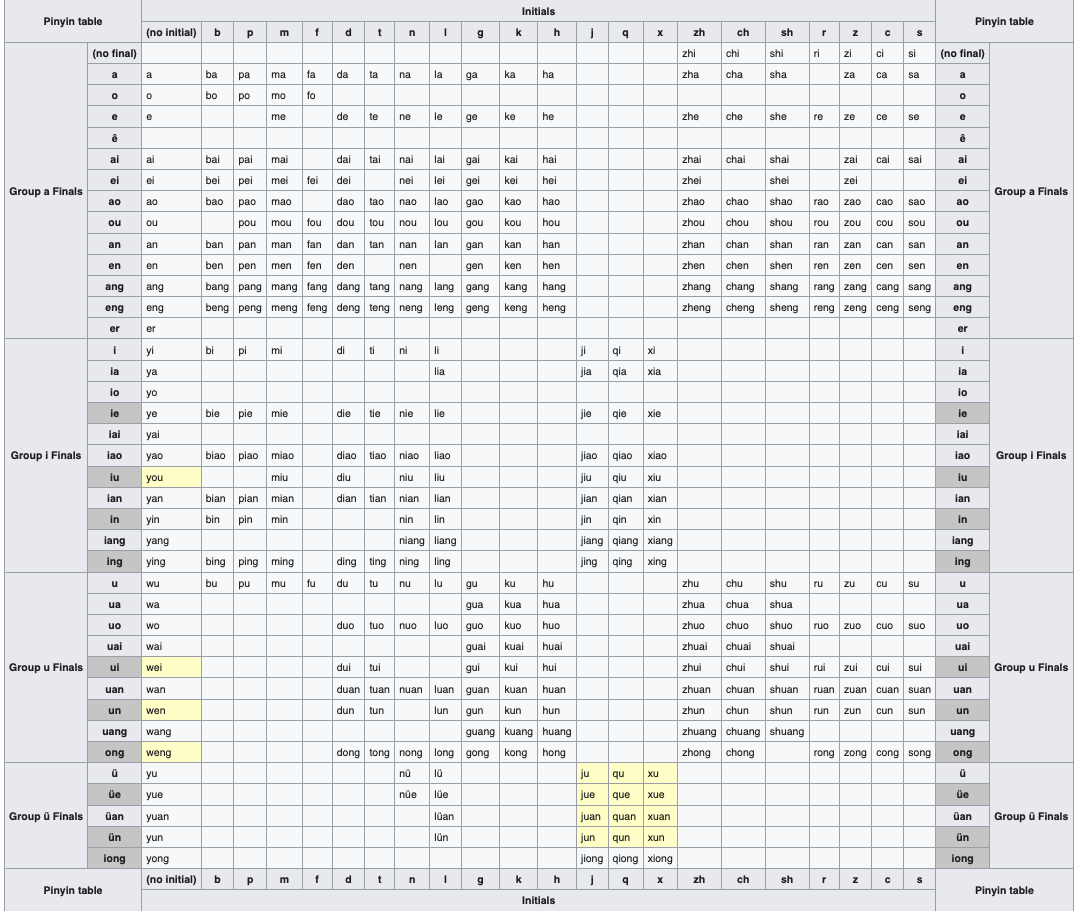

Initials

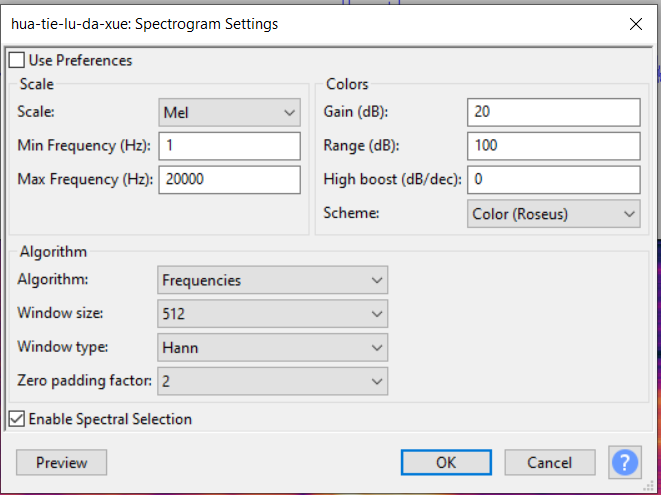

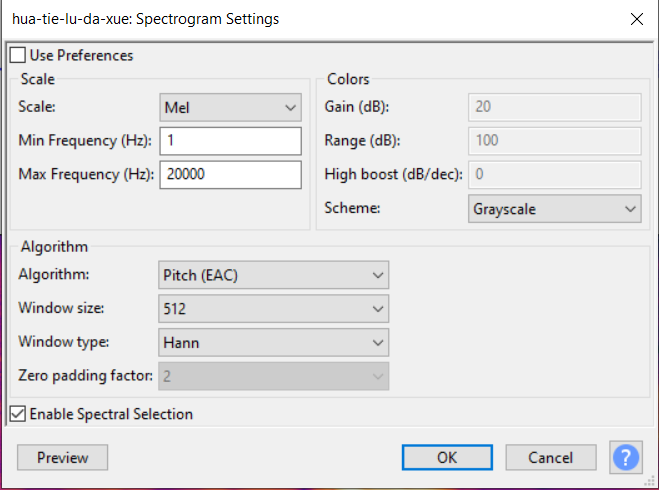

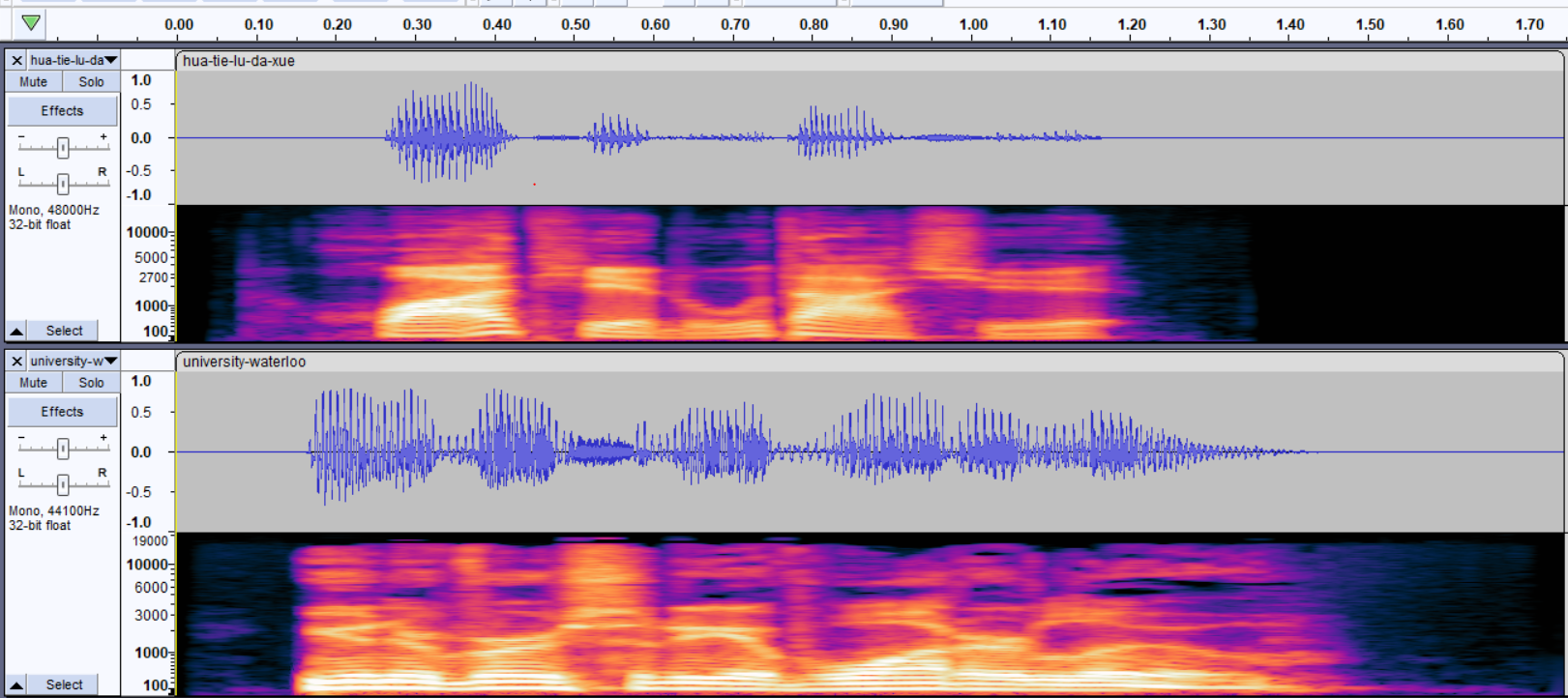

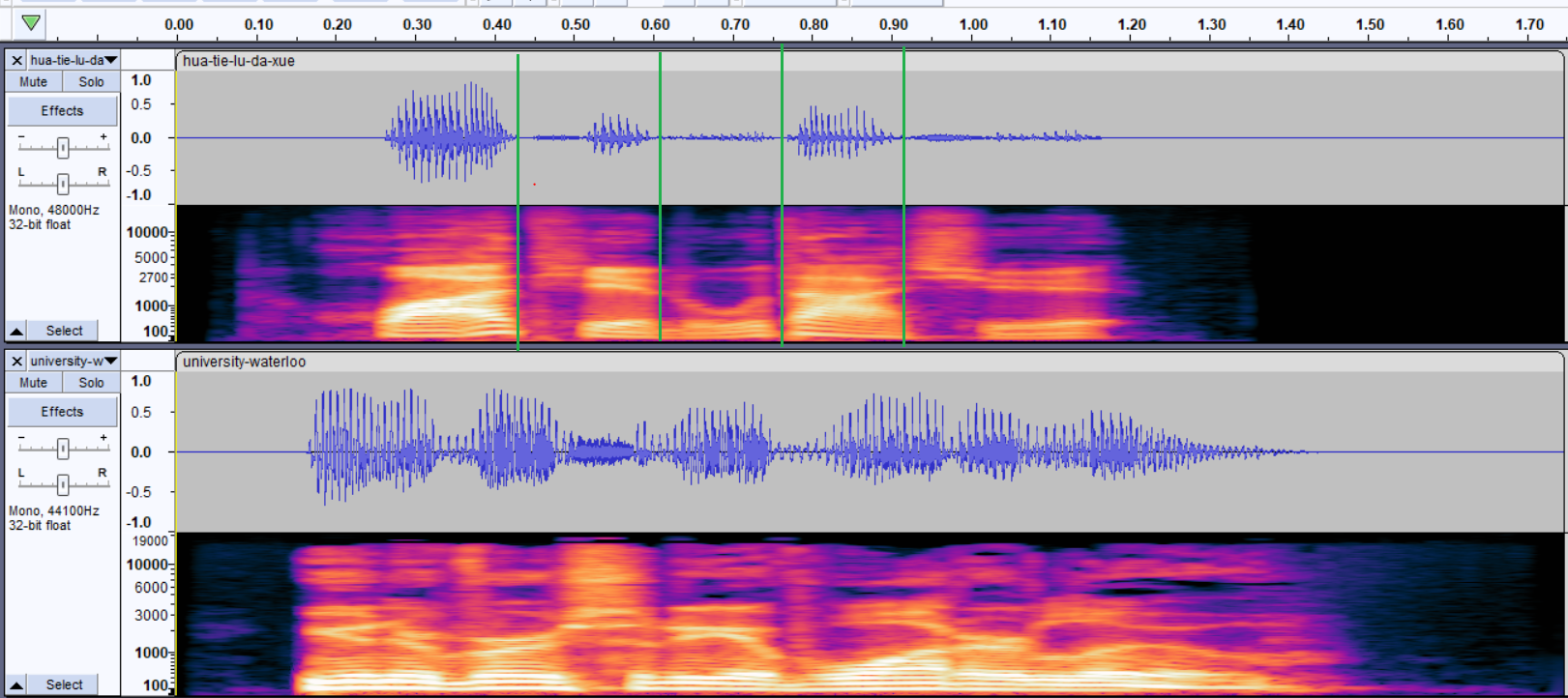

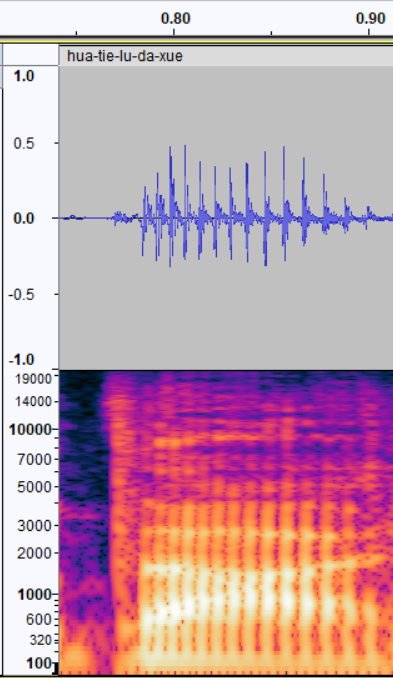

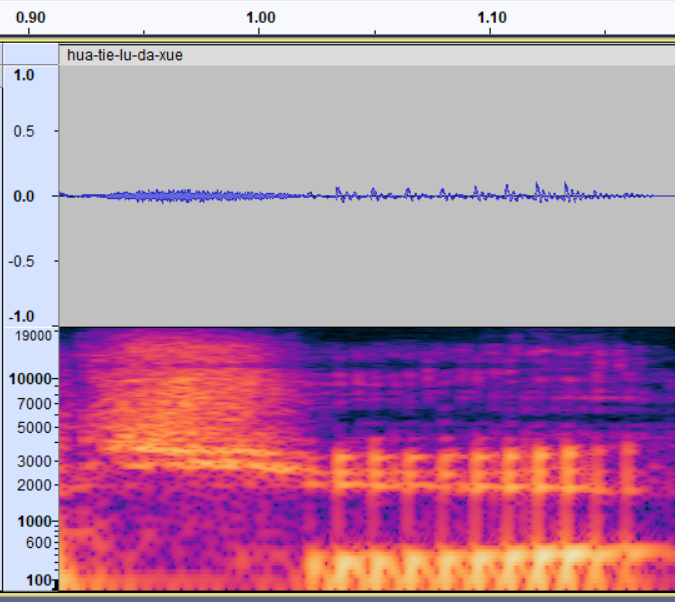

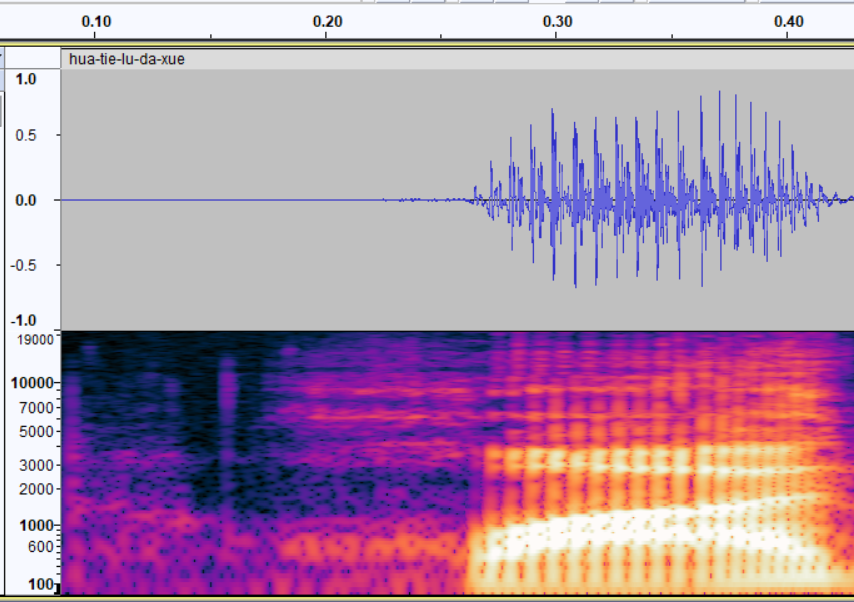

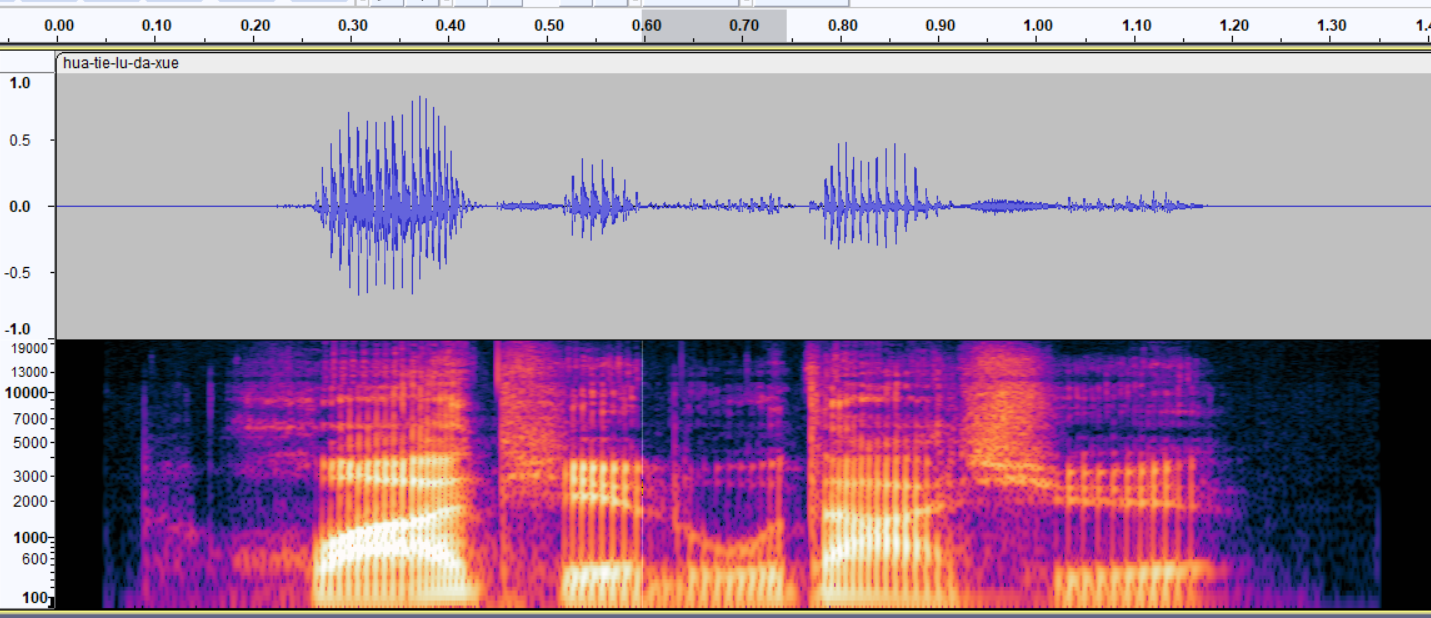

In this section, I will use two Chinese audio clips to analyze the initials in Chinese. The first item is the English translation of “University Waterloo”, “huá tiě lú dà xué”. The second passage is chinese digits counting from 1 – 10, yī èr sān sì wǔ liù qī bā jiǔ shí.

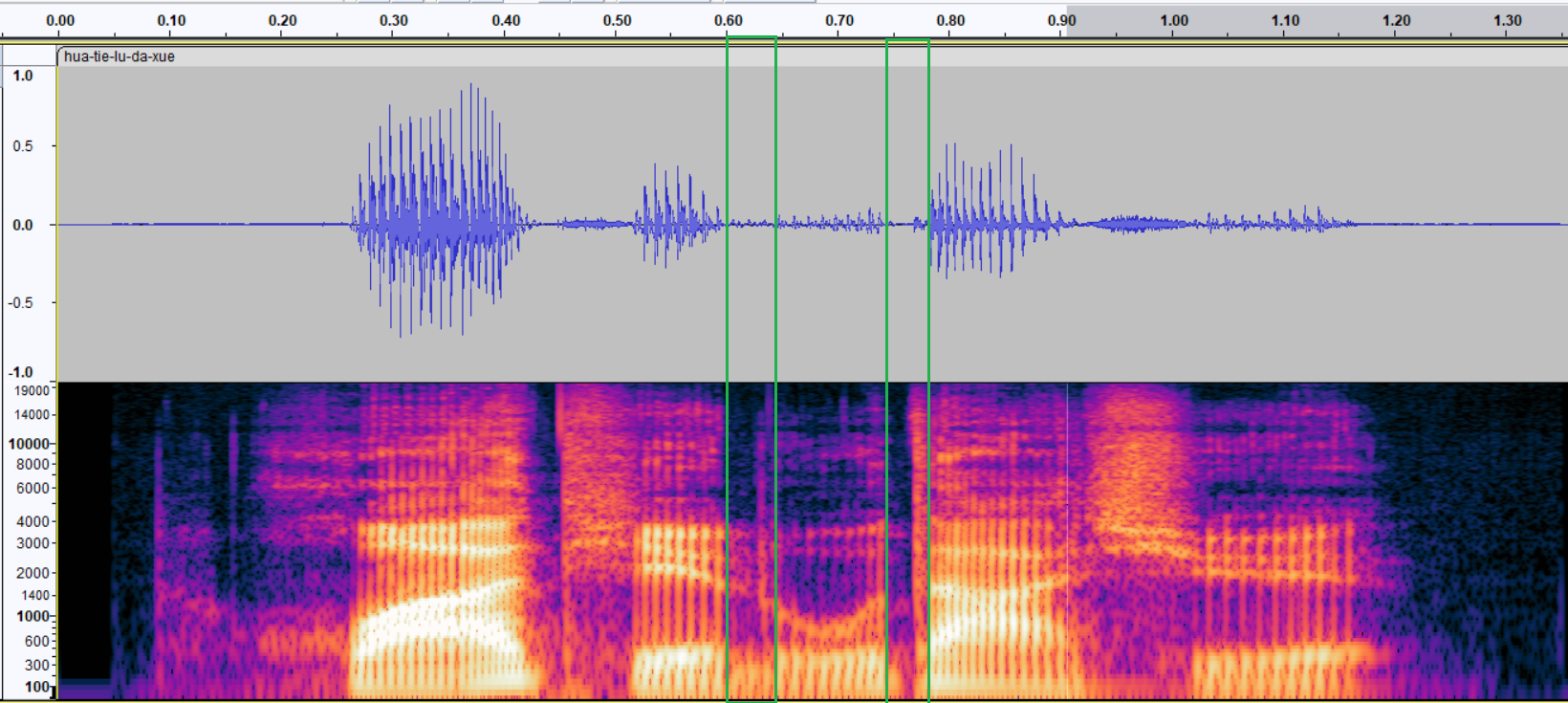

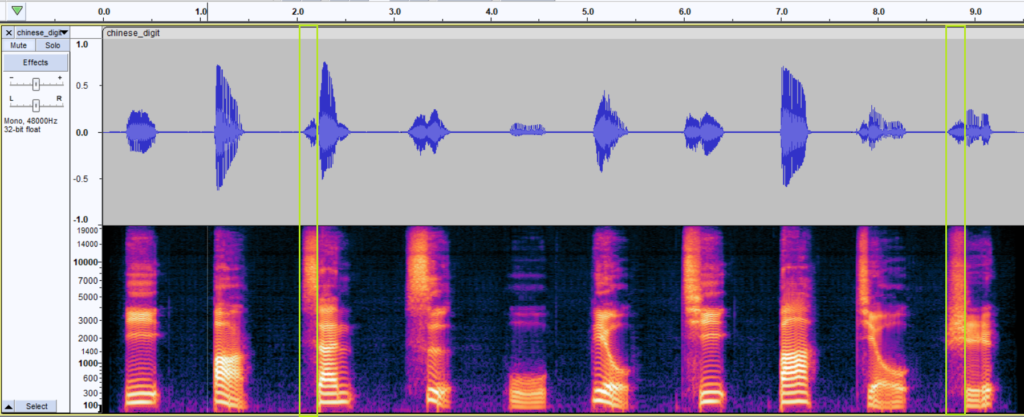

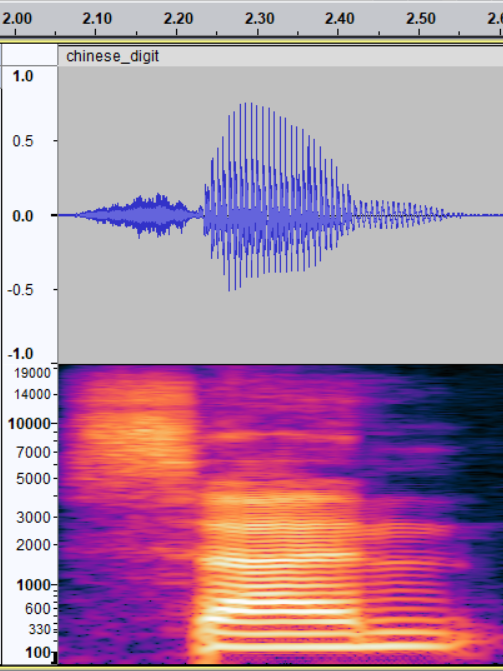

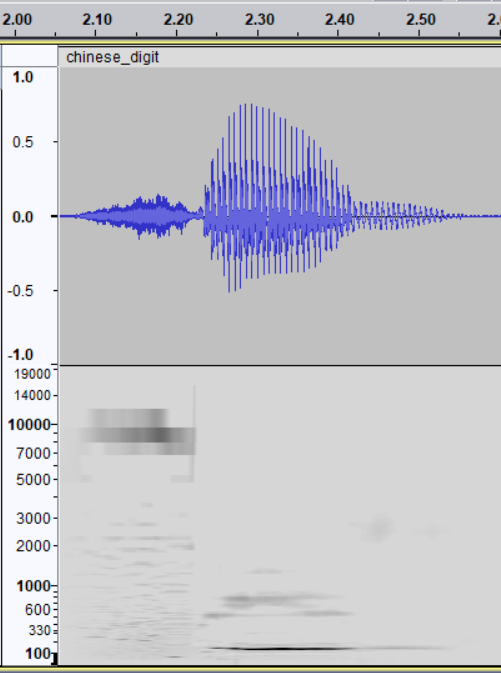

chinese digit sound 1 – 10

We will start from the scenario 1: where the initial is followed by only one vowel. In the first sample, it is ‘lu’ and ‘da’. In the second sample, I will use ‘sān’ and ‘shí’.

From these three examples, it can be seen that “l, d” are short consonants, while “s” and “sh” are long consonants. The spectrum of each consonant is also different.

s

l

d

We can see that, apart from being relatively broad, the energy of the “sh” sound is concentrated in the higher frequency area, between 2000-8000Hz. Moreover, its high-frequency energy does not show significant attenuation. In addition, “sh” also possess a higher energy distribution in lower frequencies than “s”. “s” however, has slightly more energy over the really high frequencies than “sh”.

Regarding the “d” sound, it is observed that there is a sharp increase in energy over a short period. Additionally, compared to “t,” “d” has more low-frequency energy because of vocal cord vibration.

The “l” sound is a voiced sound, so the vocal cord vibrations produce more low-frequency energy in the spectrum. At the same time, the energy roll-off in the high-frequency part of the “l” sound spectrum is not particularly pronounced.

first box: ‘s’, second box: ‘sh’

spectrogram of tiě, showing the transition from t -> ti -> iě

spectrogram of xué, showing the transition from x -> xu -> ué

Initial -- Final Transition

The third part is primarily composed of vowels and sometimes includes codas. The vowel region displays clear formant peaks on the spectrogram, which I will detail in subsequent sections. These formant peaks reflect the bright frequencies of vowels.

The second part is particularly intriguing as it demonstrates the combination of consonants and vowels. On the spectrogram, this section differs from the first two parts. Compared to pure consonants, the frequency density here is higher, yet it lacks the especially prominent bright frequencies relative to the pure vowel section. This indicates that in this transition part, we witness the process of moving from the clear articulation of consonants to the sound production of vowels. Overall, this section achieves a smooth transition from the initial consonant to the vowel.

hua

tie

xue

Final only

Sometimes, there does not exist initials in a word. For example, in the Chinese digits, yī, èr and wǔ does not have initials. This can be shown in the spectrum, where there is only one energy distribution.

spectrogram of yī – 1, èr – 2 and wǔ – 5, see how it differentiates from other sounds

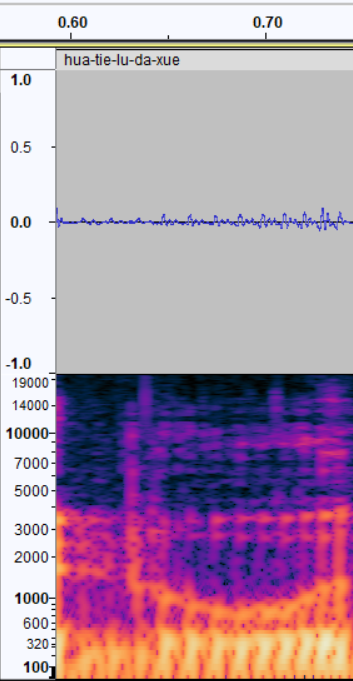

frequency spectrogram, window size = 2048

EAC spectrogram, window size = 2048

In Pinyin system for Chinese, when the letter “i” serves as a rhyme (vowel) without a preceding initial (consonant), “y” is usually added to clearly indicate the beginning of the syllable. Similarly, for the letter “u” when used as a vowel without a preceding initial, “w” is added. When “ü” acts as a vowel without an initial in front, the two dots are usually removed, and a “y” is added in the Pinyin representation.

Finals -- Tones

First Tone (High Level Tone): Marked with a macron (¯) above the vowel, indicating a high and steady pitch level.

Second Tone (Rising Tone): Marked with an acute accent (´) above the vowel, indicating the pitch rises from a medium to a high level.

Third Tone (Falling-Rising Tone): Marked with a caron (ˇ) above the vowel, indicating the pitch first falls then rises. Note that in actual speech, the third tone often manifests as a low pitch, with the rising part frequently omitted.

Fourth Tone (Falling Tone): Marked with a grave accent (`) above the vowel, indicating the pitch falls sharply from high to low.

Neutral Tone (also known as the Fifth Tone or Light Tone): Not marked with any specific tone mark, but its pronunciation is lighter and shorter, with the pitch varying depending on the preceding tone.

The first final is uá. Clearly, you can see that this spectrogram goes upwards.

The second final is iě, where there is a slight decrease in the spectrogram.

The third final is ú. As the spectrogram shown, there is a rise in tones in the end.

The fourth final, à, showing a decrease of frequency.

The fifth one ué is similar as the first one, where there is a increase in the final.

For the first tone, sān is an example. The EAC diagram clearly shows the pitch stays the same (and high) for this sound.

san

Coda

In Chinese phonetics, there indeed exists the concept of “coda”, also known as “final sounds” (尾音), but this term is primarily used in the fields of phonology and linguistics. In the phonetics of the Chinese language, a syllable can generally be divided into the initial (声母), the final (韵母), and the tone, which is inside the final. The final can further be broken down into the initial vowel part and the ending part, where the ending part is referred to as the “final sound”, coda. Codas are especially evident in some Chinese dialects that retain features of ancient Chinese pronunciation, such as Cantonese and Min Nan, which may include nasal finals (such as /m/, /n/, /ŋ/) and stop finals (such as /p/, /t/, /k/).

In Mandarin Chinese, we only keep ‘n’ and ‘ng’. And the spectrum shows below, where you can see a little ‘tail’ after the vowel, and there’s little fundamental frequency in the EAC. I have already shared the sān example, I will show the ‘shēng’ example below. ‘shēng’ has lots of meanings in Chinese. One of the meaning of it is ‘声’, which means the topic of this course (audio) !

sheng